The term ‘bodger’ appears to be a popular twentieth century name applied to turners who worked in the woodland using pole lathes. However, this term, which is usually applied to someone who ‘bodges’ or ‘botches’ his work, producing a poor result, seems a singularly inappropriate term to apply to these excellent craftsmen, and was a description probably not known to the original turners. This is reinforced since no reference to ‘bodgers’ is made in the Census returns for the High Wycombe area in either 1841 or 1851, although a few references are made in these returns to workers recorded in ‘hut in woods’. This probably refers to turners working in the woodland setting. The introduction of the word ‘bodger’ is probably a journalistic term introduced by writers in the early twentieth century when describing this craft, a word which has been erroneously repeated in subsequent texts.

Nonetheless the pictures are excellent.

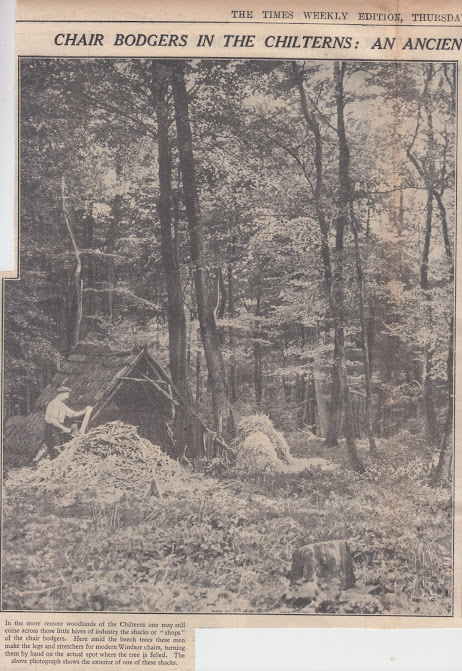

Although High Wycombe was the centre for creating many of the chair parts and assembling the completed chairs, most of the ordinary turnery work of producing the legs and stretchers required by the manufacturers, was undertaken by turners who lived in villages and hamlets of the Chiltern Hills, close to the source of wood, and who sold their work to the factory owners. This turnery trade arose particularly a few miles to the north west of High Wycombe in the forested hills in the area of Stokenchurch, Chinnor, Bledlow Ridge, Princes Risborough, Great Hampden, Radnage, and Beacon’s Bottom. In the late nineteenth century, the turners bought their wood at annual sales of standing timber which was sold by auction at the Stokenchurch Hotel. Here, estate owners would offer a ‘fall’ of twelve to twenty beech trees which, when sold, would be felled by the vendor, usually during the winter when the sap was low. The turners would then be responsible for sawing the trunks into lengths suitable for leg and stretcher turning, and lopping and burning up the unwanted branches. Some of these turners preferred to make a rough shelter at the woodland site from wood, bracken and the woodshavings they produced. Here, the turner used a froe or fromard to split the wood and a side axe to roughly shape the section. Then a draw knife, used in conjunction with a simple wooden draw horse, was used to further shape the segments, and the green wood was finally turned on a pole lathe. The resulting unseasoned, turned legs and stretchers were stacked in neat piles or poked into a ‘hedgehog’ of legs to dry. The lives of woodland turners [...] must have been lonely, although an insight into one chair turner’s thoughts and life, when looking back over the years, is sensitively given by Mr George Dean, brother of Owen Dean of Great Hampden, who was one of the last turners to work in the Chiltern Woodland. George Dean expressed himself thus:

‘It was a strangely enjoyable life, carefree and a bit lonesome if your mate was away. In the spring it was lovely as the trees took on their fresh green leaf, and in the winter, the sighing of the wind and the sight of the birds gathering in the branches when the smoke ascended at meal times. Occasionally the robins would build by the lathe side in the thatch, and hatch the eggs and rear the young. Now and then a wren would make a cosy nest and flit about. Once a flock of pigeons descended on the trees round our shops just after dark. The noise of their flapping wings was alarming as they settled in the tree tops, too exhausted to heed us very much as we worked by candlelight in our primitive way.

However, the majority of the turners preferred to work in a shed near to their homes, rather than work in the woodland, and to use a metal foot-treadled lathe, with a reciprocating flywheel, rather than a pole lathe [...] Elderly relatives of craftsmen who remember the chair turning trade in the village of Radnage recall that it was the children’s job to push freshly turned legs into the hedges around the cottage gardens to dry, and then to count them into sacks ready for the chair manufacturers from High Wycombe, who collected them by horse and cart.

|

| From The Times Weekly Edition 23 October 1930 |

Detail of the side axe in use:

|

| From The Times Weekly Edition 23 October 1930 |

Detail of the pole lathe in use:

|

| From The Times Weekly Edition 23 October 1930 |

© Julian Parker 2021 with thanks to Dr B. D. Cotton.